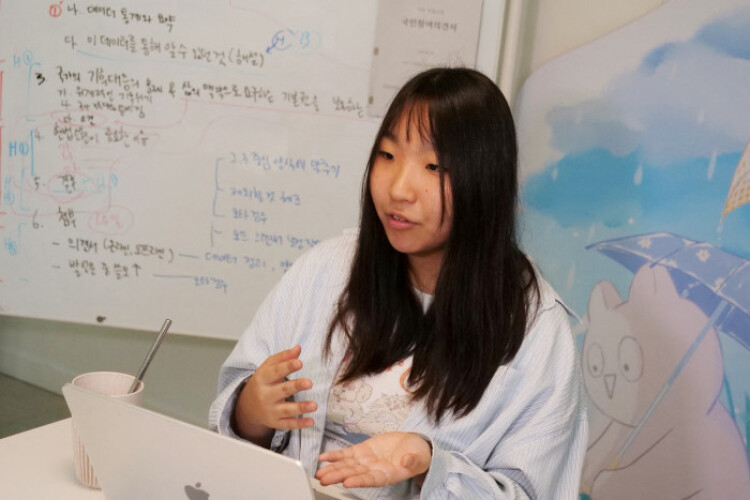

SEOUL - Yoon Hyeonjeong, a 19-year-old South Korean activist, says the fate of her years-long fight for more action to tackle climate change hinges on what could be a landmark ruling by the country’s top court on Thursday.

Yoon is among about 200 plaintiffs, including young environmentalists like herself and even infants, in petitions filed to the Constitutional Court since 2020, which argue the government is violating its citizens’ human rights by not effectively tackling climate change.

Climate advocacy groups say it will be the first high court ruling on a government’s climate action in Asia, potentially setting a precedent in a region where similar lawsuits have been filed in Taiwan and Japan. In April, Europe’s top human rights court ruled the Swiss government had violated the rights of its citizens by failing to do enough to combat climate change.

“Picketing on streets, policy proposals, these campaigns weren’t enough to bring about real changes,” said Yoon, who is hoping the court ruling will help tear down bureaucratic hurdles on climate policy.

Lawyers for the government say authorities are doing everything possible to cut carbon emissions.

Han Wha-jin, who was environment minister, said in May the government’s emission reduction targets did not infringe on people’s rights, though the constitutional petition provided a public forum about the severity of the climate crisis.

In 2019, Yoon was in her third year of middle school when she watched a climate crisis documentary that she said shocked her into action.

Despite not being particularly outgoing, she decided to try and follow in the footsteps of the likes of Greta Thunberg, a Swedish climate activist who has inspired a global youth movement demanding stronger action against climate change.

Yoon wrote slogans with crayons to picket at schools, telling her elders to stop destroying the planet. She later dropped out of high-school and left her hometown to focus on the climate movement in the capital Seoul.

South Korea’s constitutional court does not award damages or order law enforcement measures but can rule existing laws are unconstitutional and request parliament to revise them.

Germany’s constitutional court ruled in 2021 the country must update its climate law to set out how it will bring carbon emissions down to almost zero by 2050.

Scientists say a global temperature rise beyond 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above the preindustrial average will trigger catastrophic and irreversible impact on the planet, from melting ice sheets to the collapse of ocean currents.

South Korea is seeking to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, but remains the second-highest coal polluter among G20 countries after Australia, data showed, with slow adoption of renewables.

The country last year revised down its 2030 targets for greenhouse gas reductions in the industrial sector but kept its national goal of cutting emissions by 40% of 2018 levels.

Calling for an end to the use of fossil fuel, Yoon said flooding and rising temperatures caused by climate change were having immediate effects on people’s lives.

“We already have tools to cut carbon emissions. That is, stop using fossil fuels,” she said.

Yoon is among about 200 plaintiffs, including young environmentalists like herself and even infants, in petitions filed to the Constitutional Court since 2020, which argue the government is violating its citizens’ human rights by not effectively tackling climate change.

Climate advocacy groups say it will be the first high court ruling on a government’s climate action in Asia, potentially setting a precedent in a region where similar lawsuits have been filed in Taiwan and Japan. In April, Europe’s top human rights court ruled the Swiss government had violated the rights of its citizens by failing to do enough to combat climate change.

“Picketing on streets, policy proposals, these campaigns weren’t enough to bring about real changes,” said Yoon, who is hoping the court ruling will help tear down bureaucratic hurdles on climate policy.

Lawyers for the government say authorities are doing everything possible to cut carbon emissions.

Han Wha-jin, who was environment minister, said in May the government’s emission reduction targets did not infringe on people’s rights, though the constitutional petition provided a public forum about the severity of the climate crisis.

In 2019, Yoon was in her third year of middle school when she watched a climate crisis documentary that she said shocked her into action.

Despite not being particularly outgoing, she decided to try and follow in the footsteps of the likes of Greta Thunberg, a Swedish climate activist who has inspired a global youth movement demanding stronger action against climate change.

Yoon wrote slogans with crayons to picket at schools, telling her elders to stop destroying the planet. She later dropped out of high-school and left her hometown to focus on the climate movement in the capital Seoul.

South Korea’s constitutional court does not award damages or order law enforcement measures but can rule existing laws are unconstitutional and request parliament to revise them.

Germany’s constitutional court ruled in 2021 the country must update its climate law to set out how it will bring carbon emissions down to almost zero by 2050.

Scientists say a global temperature rise beyond 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above the preindustrial average will trigger catastrophic and irreversible impact on the planet, from melting ice sheets to the collapse of ocean currents.

South Korea is seeking to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, but remains the second-highest coal polluter among G20 countries after Australia, data showed, with slow adoption of renewables.

The country last year revised down its 2030 targets for greenhouse gas reductions in the industrial sector but kept its national goal of cutting emissions by 40% of 2018 levels.

Calling for an end to the use of fossil fuel, Yoon said flooding and rising temperatures caused by climate change were having immediate effects on people’s lives.

“We already have tools to cut carbon emissions. That is, stop using fossil fuels,” she said.